Weaving the History of Toba: From Ancient Volcanic Eruptions to a UNESCO Global Geopark

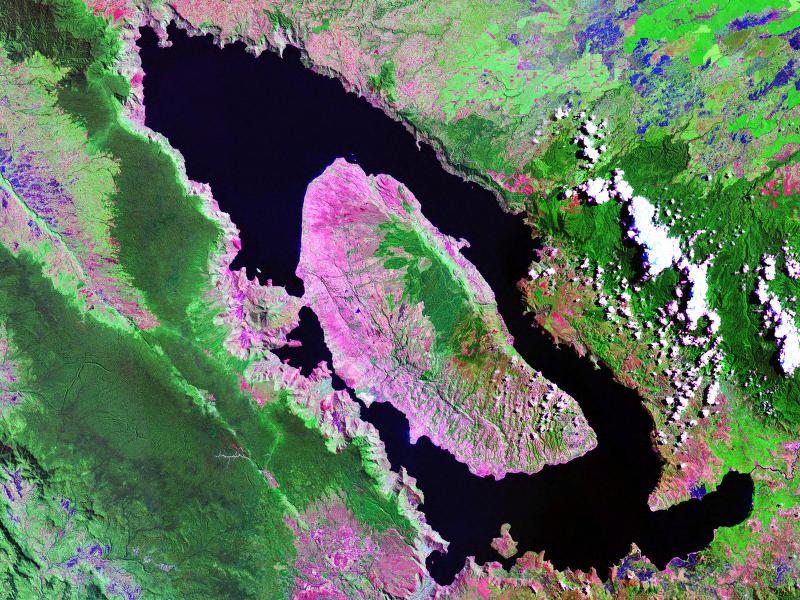

- Lake Toba was formed from the caldera of an ancient volcano, which last erupted about 74,000 years ago. The eruption spanned thousands of kilometers, from the Indian subcontinent to southern China.

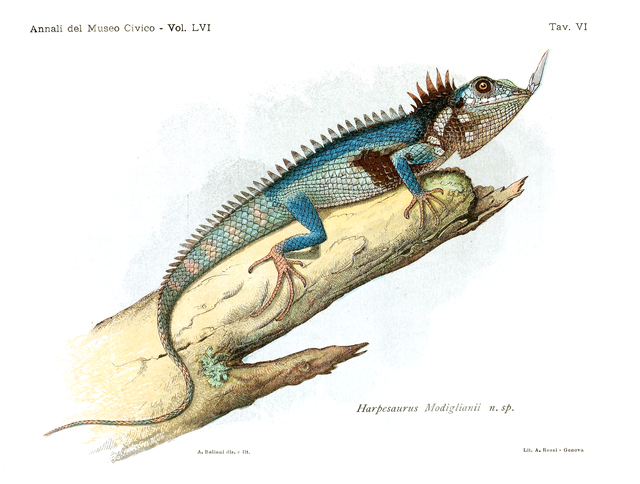

- Lake Toba holds a wealth of biodiversity, from the rare Batak fish (Neollissochilus thienemannie) to the horn-nosed lizard (Harpesaurus modiglianii Vinciguerra), which was recently rediscovered after 130 years.

- Myths and legends about Lake Toba also thrive among the local community. These stories personify the creation of Lake Toba and Samosire island in the lakes centre.

- Environmental degradation around Lake Toba has prompted the designation of the Toba Caldera area as a Global Geopark, which has been established since 2020. Management challenges are now a focus for stakeholders.

A Brief History of Lake Toba

Lake Toba, the largest volcanic lake in Southeast Asia, sits at an altitude of 900 meters above sea level in North Sumatra. Covering an area of 1,130 square kilometres, the lake stretches approximately 100 kilometres in length and 30 kilometres in width, with depths reaching up to 508 meters.

The ancient Toba volcano erupted around 74,000 years ago, in one of the largest known supervolcanic eruptions (Petraglia & Korisettar, 2011). The volcanic ash covered vast areas, from the Arabian Sea to southern China, making it even more powerful than the Tambora or Krakatoa eruptions.

The impact of the Toba eruption extends beyond geology. Paleoanthropologists, archaeologists, and geneticists study its effects on human evolution and the distribution of Homo sapiens. This period also saw humans coexisting with other species such as Neanderthals, Denisovans, and Homo floresiensis. The eruption’s climatic impact may have even influenced the decline of various Homo species.

The existence of Toba as an ancient volcano was first revealed by Dutch geologist Reinout Willem van Bemmelen in 1939. His research found pumice stones around Lake Toba and rhyolitic ash dating back to the same period as Toba’s rocks in Malaysia and India. Further research by Craig Alan Chesner and John Westgate in the 1990’s confirmed that Toba’s ash spread worldwide.

Biodiversity of Lake Toba

Lake Toba’s unique geology fosters rich biodiversity. The endangered Batak fish (Neollissochilus thienemannie) is native to the lake and its rivers, breeding in clear water sources. In 2021, the government listed this fish as a protected species due to its alarming population decline.

The Lake also holds a rich diversity of amphibian species, including the horn-nosed lizard (Harpesaurus modiglianii Vinciguerra) which was rediscovered in 2020 after being declared extinct in 1891.

Additionally, Andaliman (Zanthoxylum acanthopodium), a spice endemic to North Sumatra and commonly used in Batak cuisine, thrives in the high-altitude regions surrounding the lake.

Cultural Heritage and Legends

Several ethnic groups live around Lake Toba, including the Batak Toba, Karo, Simalungun, and Pakpak. Their culture emphasizes togetherness and openness to newcomers, reflected in their welcoming greetings: “Horas Jala Gabe” (Toba), “Mejuah-juah Kita Kerena” (Karo), and “Njuah Juah” (Pakpak).

Local legends add to the lake’s mystique. One story tells of a man named Toba who married a beautiful girl named Putri, who was a fish cursed by a god. They had a son together, who was named Samosir. When Toba revealed Putri’s secret, she and Samosir disappeared. The legend says that Toba’s tears formed Lake Toba with Samosir Island in its centre.

Environmental Degradation and Conservation of Lake Toba

Despite its ecological richness, Lake Toba faces threats from pollution, industrial waste, and invasive species. For example, the water hyacinth weed covers many parts of the lake due to its uncontrolled growth. Such challenges underpin the importance of conservation efforts to preserve the lake’s natural beauty and biodiversity.

The initiative to designate Lake Toba as a UNESCO Global Geopark began with concerns about environmental degradation from deforestation, pollution, industrial development, and mining. The Toba Caldera was officially recognized as a Global Geopark during the 209th Session of the UNESCO Executive Board in Paris, on July 7th 2020.

“Achieving UNESCO Global Geopark status is challenging,” explained geoscientist Jonathan Tarigan.

“First proposed in 2009, it required forming a dedicated team in 2013 and addressing issues like community empowerment and master planning before final approval in 2020,” Jonathon added.

The Toba Caldera Geopark integrates geodiversity, biodiversity, and cultural diversity. It encompasses 16 geological sites across six districts, including Sipisopiso, Tongging, Tuktuk Peninsula, Puncak Uludarat, Sibeabea, Pusuk Buhit, Samosir Island, Uluan Peninsula, Hutaginjang, Bakkara Bay, and Tipang Valley.

To qualify as a Global Geopark, an area must meet global geological standards and focus on three pillars: local community empowerment, education, and conservation.”The development of the Toba Caldera Geopark is not solely about tourism but encompasses various aspects,” Tarigan concluded.

The Future of Lake Toba

Lake Toba is a natural wonder of immense geological, ecological, and cultural significance. Conservation efforts are crucial to preserving its unique biodiversity and heritage. Supporting these initiatives helps to protect Lake Toba and preserve its beauty and history for future generations.

Join us in our mission to conserve Lake Toba. Your support can make a difference in protecting this incredible natural and cultural treasure. Visit our website to learn more about our conservation efforts and how you can help.